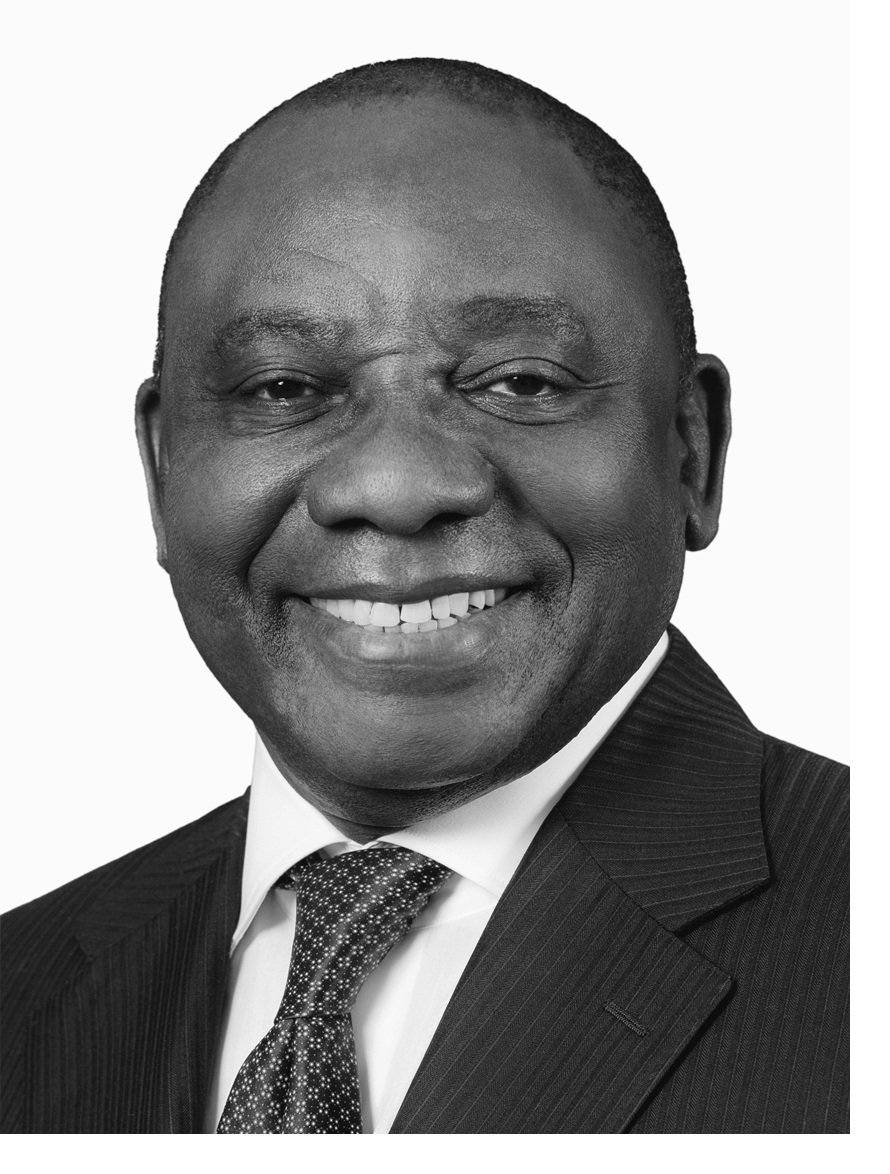

Address by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the 2019 Basic Education Sector Lekgotla, Birchwood Hotel, Ekurhuleni

Programme Director,

Minister of Basic Education, Ms Angie Motshekga,

Deputy Minister of Basic Education, Mr Enver Surty,

MECs for Education from all our nine provinces,

Leaders of teacher unions and school governing bodies,

Representatives of learner organisations,

Academics and experts in the education sector,

Representatives of non-governmental organisations,

Members of the media,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am indeed honoured to address this important Lekgotla, which brings all the key stakeholders in basic education together to find lasting solutions to some of the stubborn challenges in education.

In placing the spotlight on education matters today, we acknowledge the dynamic leadership of the Minister and Deputy Minister, the hard and strenuous work done by our officials at the Department of Basic Education, the nine provincial education departments, the 75 districts, the pivotal role of the more 400,000 teachers and principals, and the profound support of parents and partners, in the effort to provide real quality education to 12 million learners.

Appreciating that every child is an important national asset, this Lekgotla commits the government and its social partners to take our children on an exciting and meaningful journey of learning – from which our children will emerge with the knowledge and skills necessary to better respond to the challenges of a changing world.

We are here to discuss and agree on the steps we will take collectively in the year 2019 and beyond to make basic education a more effective and efficient platform for the creation of an intellectually empowered youth that is ready for higher forms of learning.

It is at the basic level of education where we must inculcate and embed the culture of learning; where we must produce children who are obsessed with consuming existing knowledge and create a burning desire among them to produce new knowledge.

This we must do while simultaneously working to build a citizenry that is conscious of, and committed to, the ideal of a truly united nation underpinned by non-racialism, non-sexism, democracy and shared prosperity.

Without quality basic education, our country cannot grow and develop, we cannot redress the injustices of the past, and we cannot build a socially cohesive nation.

Despite the challenges, we are making progress.

The class of 2018 did us proud by achieving the highest national pass rate recorded – that of 78.2%.

The analysis of the NSC examination results shows that the bulk of the improvements have occurred in historically disadvantaged schools.

The proportion of successful candidates from ‘no fee’ schools who received bachelor passes was far greater than among those from more affluent schools.

The NSC qualification continues to grow in inclusivity and diversity with the growth of technical subjects.

In a historic first, during the 2018 NSC examinations, deaf learners had the opportunity to write South African Sign Language as a Home Language as an examinable subject.

One reason why we are excited about the general upward trend in our Grade 12 results is that we know this is a manifestation of improvements occurring at all levels of the schooling system.

International trend study data point to ongoing improvements over the last 10 to 15 years in what our learners know and can do at the primary and lower secondary levels.

However, we understand that we have a long way to go, and we have not yet arrived at where we want to be.

As we mark 25 years of democracy, our actions will continue to be anchored on our recognition of education as a key driver of fair and sustainable development.

Working together, we must strive to ensure that our children excel from an early age, especially in the prioritised areas of science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics, popularly known as STEAM.

This will better prepare them for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Globalisation, technological disruption and digitisation are re-shaping the way people live, work, socialise, share knowledge and participate in increasingly complex, dynamic and diverse societies.

This creates new global challenges – like the changing nature of work – and can exacerbate existing ones – like poverty and inequality.

However, these social and economic trends also offer opportunities for wider access to information, innovation, higher productivity and a better quality of life for all.

Now more than ever before, we need to think holistically about the development of children.

From early childhood development to senior years in the schooling system, a vibrant learning environment must exist that frees the potential of our children.

We must ensure that the limited resources we have are effectively allocated and spent in the interests of future generations.

We must place strong emphasis on a vibrant learning environment because there is nothing more disastrous than schooling without learning.

It is a terrible waste of resources and of human potential.

Worse still, it is an injustice that deprives children of the rights enshrined in our Constitution.

Without learning, our children will be trapped in lives defined by poverty and economic exclusion.

In this regard, we are concerned by what our participation in the regional and international assessment benchmark studies has revealed, which is that learning conditions are almost always much worse for children from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds.

Part of dealing with this challenge is to ensure that the best teachers emerging from our universities do not all end up teaching in the already advantaged parts of the schooling system.

Getting quality teacher development to be more equitably distributed across the system is something that will not happen automatically or by accident.

It needs careful and deliberate planning, and a proper sense of the various incentives – both financial and non-financial – which influence the choices teachers make.

It is important that the education we give our children keeps pace with societal and technological change.

We recognise that the changes in the labour market and the world of work will have profound implications on learning systems.

Emergent knowledge and 21st century skills have to be included in the curriculum at all education levels.

The redesign of modern curricula requires higher flexibility through evidence-based research, stakeholder involvement and innovation.

Current initiatives, such as the three-stream curriculum model, are promising.

This approach needs to be subjected to thorough evaluation and careful and cost-sensitive planning.

Our education system must aim to create complete human beings.

In this regard, greater attention must be given to life skills and psycho-social support for learners.

The sector needs to support learners in improving their life skills relating to sexuality, care and support, and bullying.

As we pursue the goal of equipping learners with knowledge and skills for a changing world, we seek to do so in safe learning environments.

In recent weeks, we have observed increasing levels of violence and racism in some of our schools.

We welcome the campaigns of the Department of Basic Education, working with other government entities and partners, to address issues such as social media bullying, alcohol abuse, learner pregnancy and HIV infection.

We also welcome efforts together with the departments of Arts and Culture, and Sport and Recreation, to promote national building, social cohesion, tolerance, positive values, and a culture of human rights.

We must have zero tolerance of racism, sexism, bullying, violence and other forms of antisocial behaviour in our schools.

We must stand firm against school governing bodies that deny children access to schools on the basis of their linguistic backgrounds.

We need to also mobilise our communities, civic and non-governmental organisations to prevent the vandalisation of schools as part of service delivery protests.

We cannot allow our children to be denied their right to education because we as adults have certain grievances to raise with one another.

Denying our children their right to education places the future of our country in jeopardy.

No matter the difficulties we face, we cannot continue along that path.

Another critical aspect in determining the success or failure of any school is the question of leadership.

This is a serious matter that requires careful consideration at this Lekgotla.

The point is often made that the accountability of school principals, teachers, officials and others to their managers, to communities and the broader public is too weak.

The mechanisms for ensuring accountability and promoting performance are not sufficiently developed.

There is a need to ensure there is clarity on accountability and issues such as incentives to ensure better outcomes.

In this regard, we must give attention to the National Development Plan’s ‘results-oriented mutual accountability’ framework.

This Lekgotla needs to discuss how the sector is going to make this a reality?

How should the sector’s various existing and proposed systems come together to promote a clear and logical sense of accountability?

We need a functional leadership and accountability system that involves the school management teams, the teachers, the representative councils of learners, the school governing bodies and the community members at large.

With visionary leadership, we will succeed and our education system will achieve its intended objectives.

More learners will complete their entire period of schooling.

This is a matter that must be linked to the streaming of skills and the building of a diverse and capable workforce.

We must move with greater speed and agility in promoting flexible learning pathways that ease the transition between all educational levels.

These include early childhood development, primary and secondary education, technical-vocational and technical-occupational education and training, as well as higher education and training.

We must improve the tracking and monitoring of learners transitioning through these pathways.

One change, which is likely to facilitate greatly the pathways between schools and colleges would be a General Education Certificate – or GEC – at a level below Grade 12.

I am glad that this approach – an idea put forward as far back as 1995 in one of our earliest education white papers – appears to be on the policy agenda again.

Apart from facilitating the transition from school to college, a GEC would address the current problem of hundreds of thousands of young people leaving education completely each year, with no national qualification with which to navigate the labour market.

All of this requires that we must improve the qualifications of teachers.

Teachers must know their subjects well and be able to teach them well.

As we prepare for the 6th democratic administration, the basic education sector plan needs to focus on a number of critical areas.

These include:

• early childhood development,

• developing and implementing a comprehensive strategy on improving reading,

• promoting inclusivity, efficiency and quality,

• strengthening care and support for learners, and,

• developing capabilities in data analytics, coding, the internet of things and block chain technology.

We need to do more, work harder and establish greater system efficiencies in the first five years of schooling if we are to rise to the international standards prescribed as minimum benchmarks for reading comprehension, mathematics and science.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We have set out on a path to dramatically improve the lives of our people and lift millions out of poverty through education.

This Lekgotla is a platform for researchers and experts to present their findings on pertinent education issues affecting our country, informed by current global philosophies, sound evidence, and an improved understanding of education diversity, agility and modernisation.

Emerging out of this Lekgotla, the basic education sector must tell us how to inspire among education practitioners a positive and practical theory of change that leads to improved learning outcomes.

Let this gathering embrace a new dawn, in which we boldly declare that quality basic education is the most powerful weapon that we can use to change the lives of millions of South Africans.

I thank you.