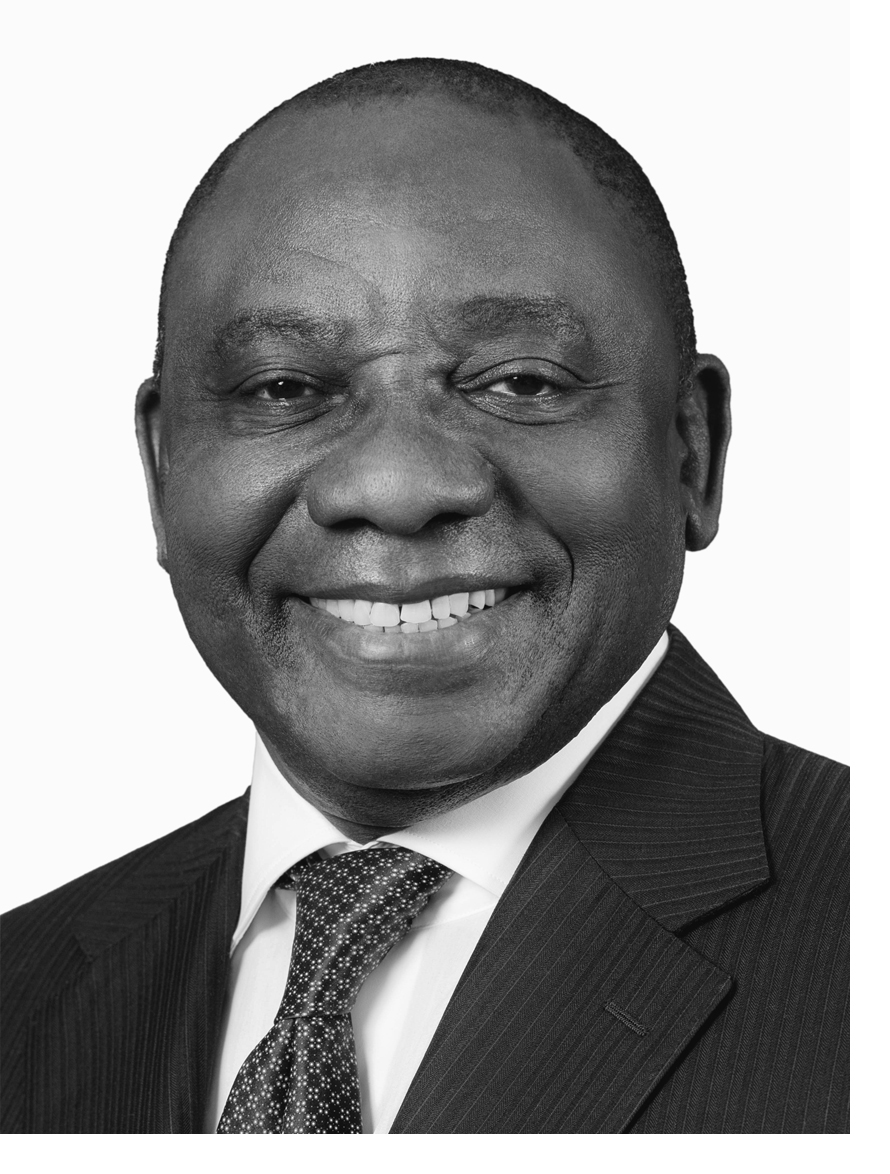

Opening Remarks by President Ramaphosa at the ADEA Annual Policy Dialogue Forum on Secondary Education in Africa, Emperors Palace, Ekurhuleni

Programme Director, Dr Mathanzima Mweli,

Minister of Basic Education, Ms Angie Motshekga,

ADEA Executive Secretary, Mr Albert Nsengiyumva,

Ministers of Education from other African countries,

Senior officials and educationalists from all corners of our continent,

Members of the Diplomatic Corps,

Representatives of the media,

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is indeed an honour and pleasure for me to welcome the Association for the Development of Education in Africa and all delegates to South Africa.

We are honoured that you granted us the opportunity to host this High-Level Annual Policy Dialogue Forum in the year in which we are celebrating 25 years of freedom and democracy.

For us, the advent of democracy – which brought about the creation of a single education system – was a major achievement towards restoring the dignity of millions of South Africans who had been denied quality education during centuries of colonialism and decades of apartheid.

This Forum’s focus on ‘Preparing Youth for the Future of Work’ reflects our understanding that Africa’s demographic dividend can only be earned through our investment in the continent’s highest-yielding resource: its young people.

I am confident that the breadth, depth and quality of discussion over the coming days will ultimately enrich the development of our continent’s human capital and move us closer to the realisation of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

We hope to share and learn from other countries on how to address the challenges.

Africa has a large proportion of young people under 25 years.

They constitute about a fifth of all people under 25 years in the world.

Furthermore, research shows that 37% of the 600 million labour force in Sub-Saharan Africa is under 25 years.

This is a great advantage for Africa, considering that most developed countries are ageing.

They need young people to work and grow their economies while contributing to taxes to subsidise social programmes for the elderly.

We in Africa can use this demographic dividend if we develop education systems that are capable, accessible and focused.

Unfortunately, our economies are unable to absorb a significant proportion of these young people, mainly because the education system is not aligned to the needs of the economy.

The unemployment rate among young people is around twice that of older adults.

Significantly, most unemployed young people across Africa are those who have completed secondary or tertiary education.

Unemployment is lower among those who have little to no education.

You may ask, how is it so?

Agriculture is the largest employer, and for now, it is labour intensive and requires workers who in most cases are without education.

Those who completed secondary or tertiary education are finding it difficult to secure employment.

Among other things, this is due to a mismatch of the skills people learn and the needs of the market.

With the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, there is a danger that this mismatch will grow.

Due to the skills deficit, our countries are ill-prepared for technological change.

We therefore need to change the direction of secondary school education if we are to develop relevant skills for the new type of economy.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is also disrupting the labour market.

The impetus for economic activity is shifting from very large enterprises to smaller individual-led companies.

An entrepreneur developing their product in a garage is now likely to create more value chain jobs than a big manufacturing company.

The manufacturing sector, while still a significant driver of growth, is not generating as many jobs as in previous decades.

We see more jobless growth because of the use of technology to replace workers.

These changes have an impact on the nature of the skills required.

Young people need foundational cognitive skills in science, technology engineering and mathematics – the so-called STEM skills – to be absorbed in the economy.

As agreed in Agenda 2063, of those who enter tertiary education institutions, 70% ideally should graduate in STEM subjects.

Digital skills, such as coding, are essential to integration in the world of work.

Such skills should be accompanied by soft skills such as emotional intelligence, interpersonal skills and excellent communication skills.

Instead of rote learning, the World Bank suggests that young people need skills in unstructured problem solving and reasoning.

Critical thinking skills are what will drive job creation and economic growth in the future.

We must change our educational systems to develop these skills.

Africa is expected to be the food basket of the world because of its geographic position and climate, and a large population of young people.

The World Bank estimates our agricultural market will be producing food and beverage worth $1 trillion by 2030.

Given that 205 million people in Africa work in the farming sector, we need to ensure that our secondary schools focus on agricultural technology.

We need to ensure that young people can both read to understand and apply knowledge in the areas of agro-processing, beneficiation of fresh produce and the standards required for food export.

Young people must have skills focusing on the agricultural value chain.

The second-largest source of jobs in Africa is the service sector, which was estimated to employ over 100 million people in 2015.

This sector includes information, communication and technology.

The sector also includes customer services, sales and human resources in areas such as entertainment, restaurants, tourism and transport.

These areas are likely to grow.

Therefore, young people need both technical skills and ‘soft’ skills.

We need to overcome some barriers if Africa wants to create future jobs.

First, we need to have educators who are skilled to function in the modern economy.

Many of our teachers were taught in the old system of rote learning.

Often, they are not able to use advanced tools of the trade such as computers.

Most were not trained to apply knowledge but were taught to accumulate knowledge.

In today’s world, information and knowledge is abundant.

The key is to apply the knowledge we have to solve problems.

Second, our educators need to know how to develop a curriculum that is relevant to the economy.

They should work in partnership with the private sector to design and implement a curriculum that augments the basic foundational skills.

Successful countries are those that ensure that the skills they produce are appropriate for their industry.

After all, the private sector will be the recipient of many of these secondary school graduates.

Therefore, they need to absorb the graduates much more easily.

Not every learner is qualified to pursue the academic track.

Countries in which 50% of their learners enter technical colleges to develop artisan skills have lower youth unemployment rates than where the overwhelming majority enter tertiary educational institutions.

The assumption we often make that every learner is destined to enter a tertiary institution needs to be re-examined, and our secondary education systems restructured accordingly.

Our schools need to form part of a comprehensive society-wide response to the challenges and opportunities of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Rapid technological advances are already having significant consequences for workers and communities, with digitisation and mechanisation of work processes giving rise to increased insecurity and job losses.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is our current reality and it waits for no man, woman, government, learner, student, employer or trade union.

As we respond to the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we should – as a continent and as a global community – put people at the heart of economic and social policy and business practices.

There are remarkable opportunities – but also challenges – emerging from the dynamic forces that are transforming the world of work.

To help global society navigate these challenges and opportunities, we need to invest in the capabilities of people.

Secondary education occupies a crucial role in our effort to set the people of our continent on a path to sustainable and inclusive development that will benefit all of humanity.

Secondary education intervenes in young people’s lives at a time when they are most energised but also most vulnerable to adverse social influences.

Secondary education empowers young people at a time when they are most hopeful, experimental and flexible in their lives, and we should embrace this life stage as one to empower young people to take charge of their lives and our collective future.

But this means getting the basics right earlier in their lives.

Without realising these goals, we stand no chance of succeeding in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or of shifting from being a continent of consumers to being a continent of innovators and inventors.

We have also committed that we will set our sights on the furthest horizons.

This does not mean living in denial of the challenges that affect us, but implementing realistic and far-reaching solutions to address them.

As host and participant in this Forum, South Africa stands to learn and gain a great deal from the discussions that will unfold here.

We look forward to the outcomes of this Forum as an impetus for changing the fortunes of young Africans and therefore the fortunes of human society at large.

I welcome you once more and wish you well in your deliberations.

I thank you.