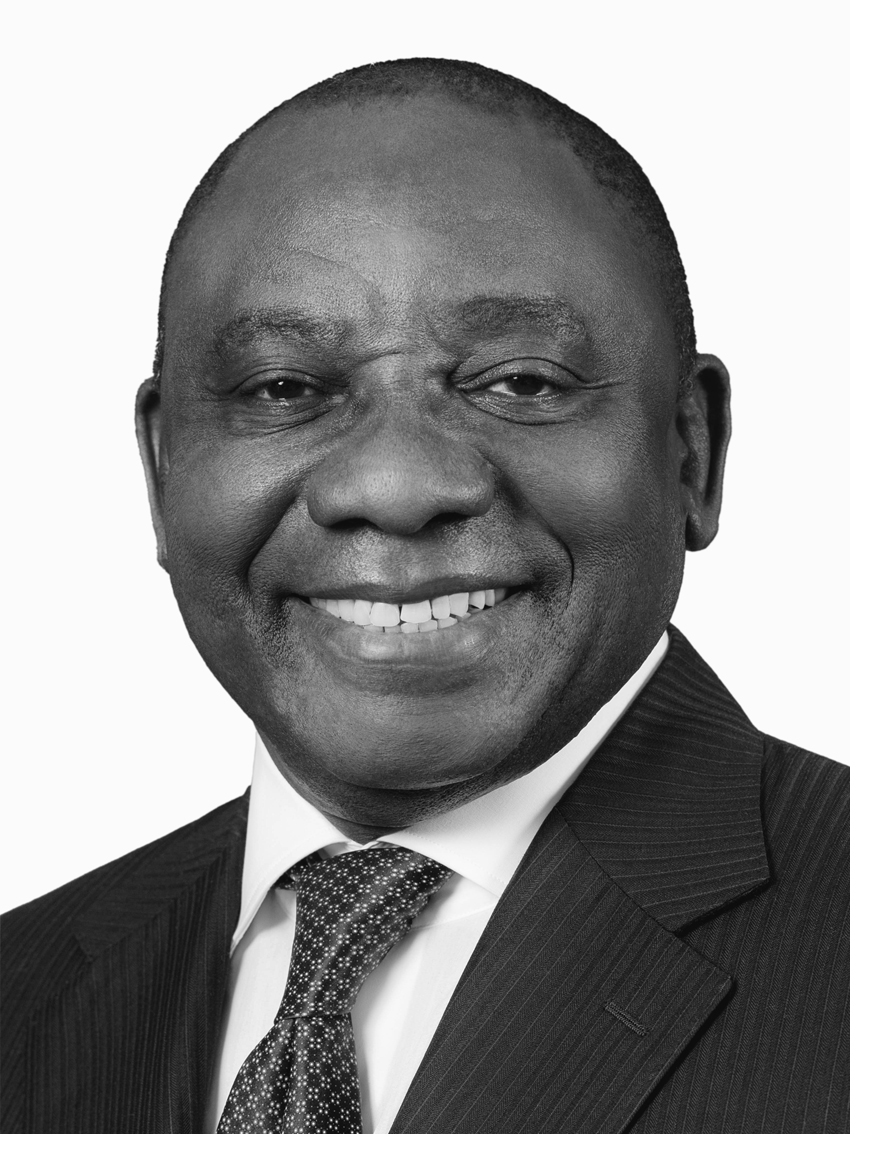

Remarks by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the 95th Birthday Celebration of Isithwalandwe Seaparankwe Andrew Mekete Mlangeni

President Thabo Mbeki,

President Kgalema Motlanthe,

Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi,

Members of the Mlangeni family,

Ministers and Deputy Ministers,

Comrades,

Friends,

And our guest of honour, our hero and father, Bab’ Andrew Mlangeni, who was born on this day 95 years ago.

Today is indeed a celebration, but also a triumph, for it is only the few who get to reach such a milestone.

Bab’ Mlangeni, we give thanks for your health and well-being and remain immensely grateful for the incalculable contribution you have made to this country and its people.

It is said that virtue is its only reward.

Today we pay tribute to a man whose life has been rich, but not in the material sense, rewarding, but not with title or position, and fulfilling, but never blighted by arrogance or conceit.

I know this is a day tinged with sadness, because there would have been a seat reserved at this birthday celebration for Bab’ Mlangeni’s dear friend and comrade Denis Goldberg.

Though we have all felt sorrow at his passing, we know it has been all the more difficult for you.

We had become used to seeing you together at national days, at rallies and other public events.

We have all marvelled at your boundless energy and enthusiasm, at your firm grasp of the issues affecting our people, and at the sheer depth of your commitment to this country.

You have been our conscience, encouraging and supporting us where we did well, and steering us back on course when we faltered.

In doing so you have been consistent and principled.

Your life has been one of struggle and sacrifice.

We know of the young man who was forced to leave school at an early age to care for his family, about a bus driver joined the worker’s struggle and then the ANC Youth League in 1951.

We know of the activist who was present at the Congress of the People in Kliptown in 1955; of the cadre who was sent to China for military training in 1961; and of the Rivonia Trialist and political prisoner who spent 26 years on Robben Island.

Then there is also the little known fact that you once moonlighted as a man of the cloth.

Very people know that in the early 1960s, when he was wanted by the police, Bab’ Mlangeni was Reverend Mokete Mokena of Dube, Soweto, replete with a certificate of priesthood, a collar and a porapora.

Using this priestly disguise he was able to travel across provinces to organise meetings and address MK structures.

I’m told it went well, except for the time he started eating at someone’s home without blessing the food, or the time he lit up a cigarette, much to everyone’s shock.

Then there are the forces that shaped him.

Bab’ Mlangeni was born into a world of segregation and dispossession where the insidious effects of the 1913 Natives Land Act deprived his family of their ancestral land, forcing them to live on three separate farms as labour tenants.

We know of the struggles that defined his early life.

To obtain an education, to find employment in the city to support his siblings, and of his grief at the loss of a father when he was still young.

There are many experiences in Bab’ Mlangeni’s life that left a deep impression on me, as told to me in our many conversations over the years or relayed in his biography, The Backroom Boy.

I reflect on them often, for they are a reminder of just how high a price was paid for the freedom we enjoy today.

Yet none has found greater resonance for me at this particular time, than the year 1946 when he finished his schooling and had to look for work, but found himself unable to do so because he did not have a dompas.

For that entire year, he recalls, he lived in fear of deportation from the Transvaal back to his rural home.

Or worse yet, of being detained and forced to work on the potato farms at Bethal.

By compelling us to carry a pass our oppressors wanted to remind us that we were unwanted and that we were strangers in the land of our birth.

In tearing them up, in burning them, in refusing to carry them no matter what the cost, we were reclaiming far more than our right to walk the streets in freedom.

We were reclaiming our very dignity.

This episode has particular resonance at this time because across the Atlantic Ocean, thousands of kilometres away, the dreaded dompas has resurfaced.

In the United States, our black brothers and sisters have embarked on a massive fight to reclaim their dignity.

The killing of George Floyd has opened up deep wounds for us all.

The struggles waged by Bab’ Mlangeni and the fighters of his generation were foremost in the service of the people of South Africa, but they were also for the cause of liberation of all who suffer under tyranny and oppression.

That is why we stand in solidarity with our African-American brothers and sisters, and express our wish that the American people can reconcile, as we did, and close once and for all the doors of racial injustice.

The dignity they seek is the dignity that Bab’ Mlangeni has fought for his entire life.

I know that it has pained him deeply to witness acts that infringe on the dignity of others.

I know that seeing our children in mud schools, seeing men and women collecting water from dirty rivers, and seeing pensioners sleeping outside pension pay-points, have aggrieved him greatly.

And he has not hesitated to speak out when necessary.

It has been of great concern to him, and is a concern we share, that 26 years into democracy we have still not fully met the developmental aspirations of our people, and that this is an affront to human dignity.

The promise of a better life for all that was made in 1994 cannot be deferred.

The process of historical redress, particularly on the land question, must be accelerated.

The transformation of the economy so that it benefits all our people must be at the centre of our national effort.

We must address the legacy of racism that has resulted in blacks living in impoverished areas far from places of work and opportunity.

We must press ahead with policies of redress and affirmative action to bring more black men and women into the world of work.

Bab’ Mlangeni, you have sounded the warning many times.

You have constantly reminded us that our impressive Constitution means little unless the rights it guarantees are fulfilled.

You have spoken at length of our responsibility as leaders of this country to meet the expectations of our people.

Unless we make this a world that is truly free of the dompas of the heart and the mind, we will never be a united nation.

Our guest of honour is the great link between our past and our future.

In his life we gain insight into the importance of loyalty to a cause, the virtue of selflessness, and of unwavering commitment to the upliftment of others.

We also draw lessons on the qualities of leadership, such as bravery, honesty, empathy, humility and being principled.

Your life has been an inspiration, to me and to many others.

Bab’ Mlangeni, we wish you the happiest of birthdays.

You are a national treasure, and we are thankful for your continuous presence in our public life and in the life of the ANC as a mentor, as a guide and, importantly, as a critic.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jnr:

“Everyone has the power for greatness, not for fame, but greatness, because greatness is determined by service.”

You have served your country and your people.

May we continue to benefit from your wisdom and counsel, and may we prove ourselves worthy of your support and confidence.

I thank you.