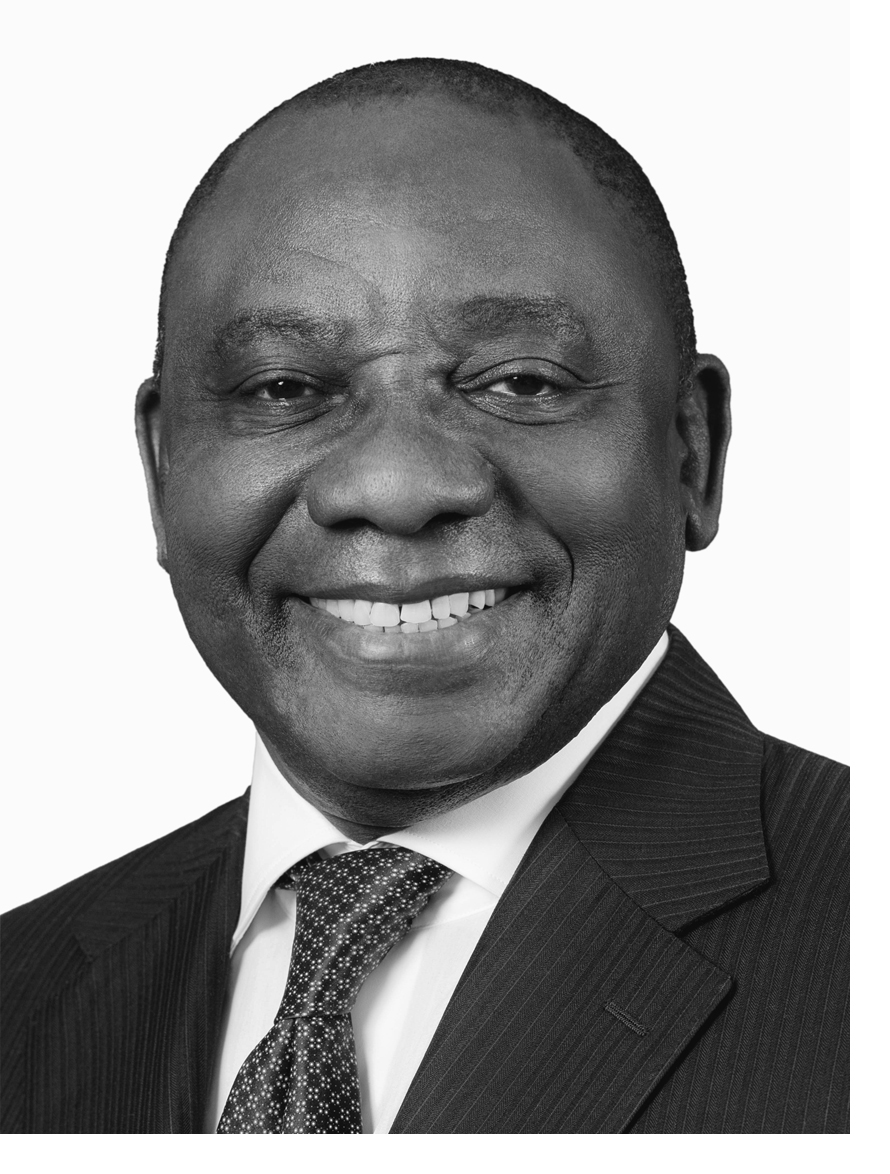

Eulogy by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the Official Funeral of Advocate George Bizos SC, Johannesburg

Programme Director,

Former President Kgalema Motlanthe,

Premier of Gauteng, Mr David Makhura,

Retired Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke,

Members of the Bizos family,

Fellow Mourners,

There are very few in our society of whom it can be said that they inspired an entire generation to follow in their footsteps.

It is not many who are of such distinguished reputation that they are known simply by their first name, not just in their own social circle but to the entire country.

It is only the rarest of individuals upon whom the title ‘champion of the oppressed’ is bestowed.

George Bizos was such a man.

A great tree has fallen.

A tree that gave shade to the patriots that founded our great nation and sheltered the poor, the marginalised and the vulnerable.

We are bidding farewell to a titan of the legal profession whose defence of the cause of justice was as tenacious as it was lifelong.

George Bizos arrived in South Africa with his father in 1941, having escaped the flames of war in his native Greece.

He was just thirteen years old and a refugee.

His was a deeply personal experience of being forced from one’s home and of being treated like a second-class citizen in the land of one’s birth.

He knew the pain of exile and of being rootless.

There can be no doubt that his personal background influenced and nourished the great well of empathy, compassion and solidarity that drove George in the practice of his craft.

He was, in his own words, a lover of freedom.

And love of freedom would put him on an inevitable collision course with the apartheid State.

He was destined to be an activist lawyer and a champion of the liberation struggle.

We read in his memoirs how it astounded him that he, a refugee from Europe, had more rights in South Africa than the black majority.

He could not and would not accept how he, a white immigrant, could be well-fed, clothed and educated while the native people of the country lived in squalour and deprivation.

His activism really began when he was a student at the University of the Witwatersrand in the late 1940s.

It was at university that he first met Nelson Mandela, and he would later go on to defend him and others in both the 1956 Treason Trial and the 1963 Rivonia Trial.

It was the start of a lifelong friendship.

President Mandela would later write that George was like a brother to him, and that he was greatly comforted that during his long imprisonment his family was being looked after by his friend.

At Wits, he joined the Student Representative Council, and soon became involved in the struggles of black students on campus.

The apartheid government punished him by denying him citizenship for over three decades.

George’s biography relates that the refusal letter told him he was “not fit and proper” to become a South African citizen.

But the rabble-rouser that he was, he would not go quietly.

He never laid claim to having been a firebrand revolutionary.

He sought neither honours nor recognition.

He did not desire fame nor did he seek it out.

Even when apartheid ended he never brandished his past to cover himself in glory and to loudly proclaim to the world ‘where he was’ during the fight for liberation.

Because he was there.

At every crucial point in our country’s history and along our path to liberation, George was there.

Quietly but also loudly; unassumingly but also forcefully.

The courtroom was his frontline. The law was his key weapon.

That he was not affiliated to a political movement does not mean he was apolitical.

He understood that to love freedom means to forever be political, and that defence of the rights of every man, woman and child is in itself a political act.

He defended freedom fighters and the leaders of the struggle because he believed in justice.

George Bizos was a man guided foremost by his conscience.

We all know of his presence at some of the most famous trials in our history.

Being on the defence team at the Rivonia Trial was a baptism of fire.

He was still a young lawyer, but he made his mark with his legal prowess and, let it be said, with his street smarts as well.

It is recorded that he forewarned the trialists that the government was planning to hand down the death penalty.

As the story is now well known, he proposed that Madiba add the words “if needs be” into his statement from the dock, averting what would for all intents and purposes been a premeditated miscarriage of justice.

Over the course of his life George defended many leaders of the liberation struggle like Trevor Huddleston, Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu.

But they were not just his clients. They trusted him and became his friends.

We also know of the role he played in the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

He was trusted by the families of Ahmed Timol, Steve Biko, Neil Aggett, the Cradock Five and victims of the apartheid death squads to represent them.

He did so faithfully, opposing the amnesty applications of the killers of Chris Hani, Ruth First, Jeanette and Katryn Schoon and many others.

Those of us who attended the hearings and even those who were watching around the world remain in awe of George’s tenacity and razor-sharp questioning that reduced the once- bold apologists for apartheid crimes to bumbling, fumbling wrecks.

But there was also the George Bizos away from the glare of the television cameras of the world.

There was the George Bizos who led the team for the Constitutional Assembly to certify the first Constitution of democratic South Africa, and who assisted in its drafting.

George Bizos brought a unique quality of personality and intellect to bear on his knowledge of the law and the Constitution of our country.

His contribution has been extraordinary and his influence on our constitutional democracy is without any doubt felt not only by those in the legal profession but by many South Africans.

There was George Bizos the philanthropist who was a founding member of the Saheti School and who established a scholarship and bursary fund for needy students.

There was George, always known fondly and simply as George to the young lawyers he mentored, who was a founding member of Lawyers for Human Rights and the Legal Resources Centre.

There was George always prepared to share the fruit of his vegetable garden, regaling young lawyers with stories of cases past, the history of the olive tree or symbols of ancient Greek history.

The ultimate purpose of the law is the guarantee of justice it promises, and George remained faithful to the notion that the law must serve the public interest above all.

During his life he mentored many young lawyers who are today prominent in their own right and are on the Bench.

Much of that learning happened outside the court room and away from chambers, in hours spent driving with him to court or over a warm, leisurely and enlightening lunch.

It seemed at times his energy was limitless.

Neither the onward march of age nor frailty could hold him from the courtroom.

He was a legendary wit of equally legendary put-downs, delivered with devastating effect to opponents during trials.

He spoke his mind and was never deferential.

He didn’t care for the airs and graces of politicians and it is said that even President Mandela got a good telling off from George on occasion.

He wore his immense stature in our society with humility and dignity.

His one-upmanship was reserved for the courtroom, never for the young lawyers, clients and even other senior counsel lined up at his door seeking help or advice.

He treated everyone as his equal and with respect – from silks and judges to the unemployed young man who had been illegally evicted, from Ministers and Presidents to the elderly woman who did not receive her grant.

He was on the right side of history.

When the democratic government fell short of its obligations, or when big business abused its power, he and his colleagues acted on behalf of the vulnerable.

For him the struggle did not end with democracy, but would only end when every man, woman and child enjoyed the rights promised them.

We owe it to his legacy to finish the business he started.

The injustices that happened under the death squads and detentions under apartheid must all be laid bare, and the dignity of those who still do not know what happened to their loved ones must be restored.

The law must continue to be an instrument of protection for the most vulnerable of our citizens, be it against individuals, businesses or the State.

The same spirit that drove young men like George to enter the profession should serve to inspire other young lawyers today to enter the field of human rights law.

George has finished his Odyssey. He has run the race.

The legal profession and the country is poorer for this great loss.

On behalf of all the people of South Africa I offer my deepest condolences to the Bizos family, and I thank them for giving us this great man.

It was said by our former rulers that George Bizos was “not fit and proper”.

If having conscience, principle and commitment and standing up for what is right no matter the cost is “not fit and proper”, may we all be granted the courage to be regarded as neither fit nor proper.

It was Archimedes of Syracuse who said:

“Give me a place to stand and I will move the earth.”

George was indeed a son of this soil. Not born of it, he was the soil itself.

We will forever remember him in his robes, rising to address the court, and smiling, leaning on his cane as he whispered to his clients and his protégés.

From where he stood, in his own unique way, he moved the earth.

He was a patriot. He was a hero.

He was the embodiment of a fit and proper South African citizen.

It was a an honour and a privilege to know you, George.

Fare thee well good friend.

I thank you.