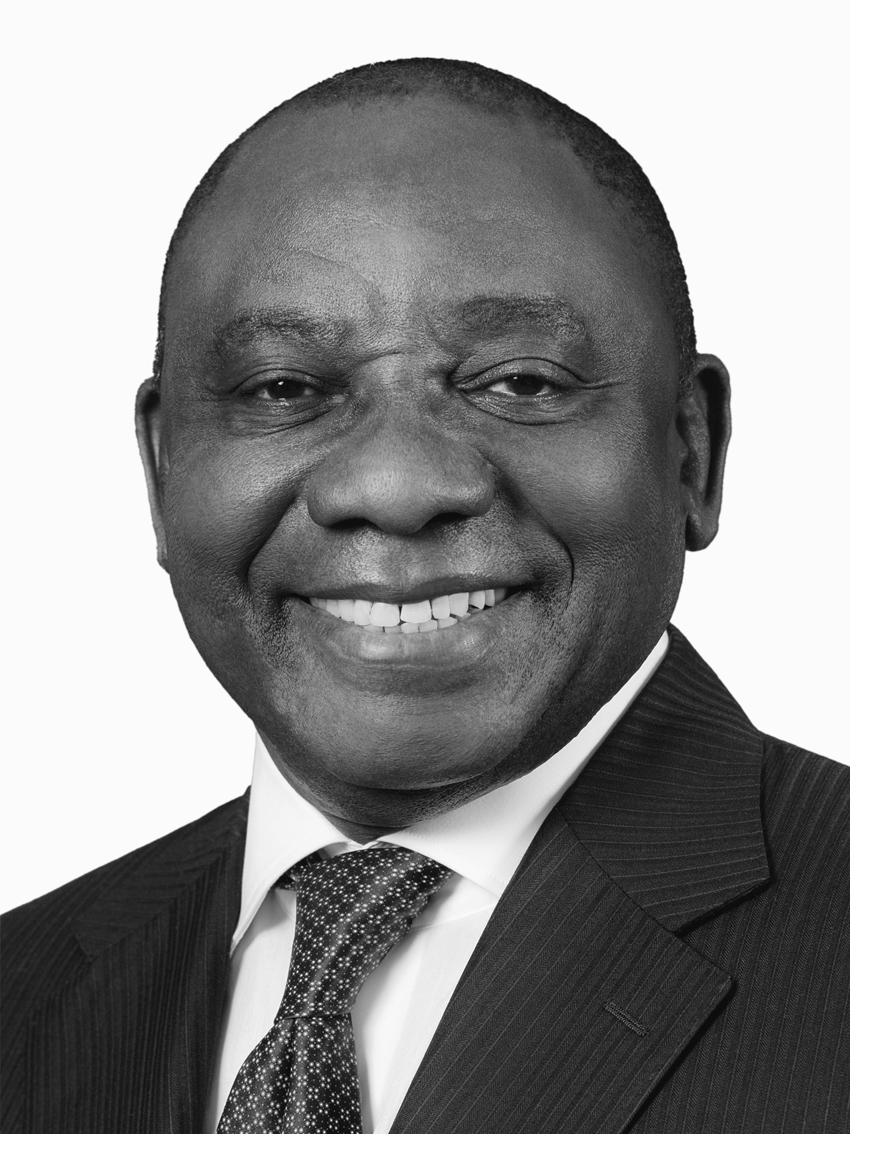

Address by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the Centenary Celebration of the Afrikanerbond Rhebokskloof, Paarl

Voorsitter van die Afrikanerbond, Mnr Jaco Schoeman, asook vorige Voorsitters,

Hoofsekretaris van die Afrikanerbond, Mnr Jan Bosman,

Lede van die Nasionale Raad,

Lede van die Afrikanerbond,

Verteenwoordigers van verskeie organisasies,

Leiers van Politieke Partye teenwoordig en Lede van die Parlement,

Ontvangers van spesiale toekennings,

Dames en Here,

Goeie naand!

Dit is vir my ‘n groot voorreg dat u my uitgenooi het vir die geskiedkundige 100 jarige viering van die bestaan van die Afrikanerbond.

[It is a great honour to be invited to address you on this historic occasion, the celebration of the centenary of the Afrikanerbond.]

Hierdie is ‘n beduidende geleentheid, wat ons as Suid-Afrikaners moet erken en waardeer.

[This is a moment of great significance, which we as South Africans must acknowledge and appreciate.]

2018 is an important year in the life of our country in more ways than many. It is a year in which we commemorate a number of key historical events that have shaped the future of our country.

The one obscure event that we should remember as a nation is what happened 210 years ago when slaves rebelled in 1808 in the Cape seeking a free state and freedom for all slaves. The rebellion, which was quashed by the colonial authorities, was one of the earliest instances of organised multi-racial resistance to tyranny and injustice in South Africa.

This year is also 105 years since the 1913 Land Act and 95 years since the Native Urban Areas Act, two pieces of legislation that were central to the deprivation of black South Africans of their land, assets and livelihoods. The effects of these laws continue to be felt today.

As the Broderbond was being formed 100 years ago the Bantu Women’s League, a forerunner of the ANC Women’s League was the first organisation in the country to take up the struggle of South African women.

It is 75 years since the adoption of the Africans’ Claims in South Africa document, which set out the demands of black South Africans for equal rights and self-determination. This seminal document was a precursor to the Freedom Charter, the ANC’s Constitutional Guidelines and the country’s democratic Constitution.

For nearly 50 years, the Afrikaner Broederbond stood at the centre of the political and economic life of South Africa.

It was a movement born out of the subjugation of the Afrikaner people by the British, the pain and resentment caused by the destruction of Boer farms and the imprisonment in concentration camps of Boer women and children.

It was born out of the suppression of Afrikaans as a language and the frustration of the economic and political aspirations of the citizens of the former Boer republics.

Yet, it is one of the greatest tragedies of South Africa in the 20th century that in pursuing the rights and freedoms that all peoples yearn for and deserve, the Afrikaner Broederbond would inevitably deny the majority of South Africans these very same rights and freedoms.

It is a tragedy that the desire of the Afrikaner people for self-determination, the preservation of their language and culture and the affirmation of their identity should have formed the basis for the perpetuation of the discriminatory practices of the colonial era.

This is a historic reality that we must acknowledge and reflect on.

We cannot not deny our history, for it lives on in the present.

We cannot change our divided past, but we can together shape our common future.

Today, the Afrikaner Bond is an organisation that is much changed.

It is not only known by a different name, but its credo reflects a desire to build an inclusive, just and truly democratic society.

It reflects a determination to forge an Afrikaner identity that is rooted in a commitment to enhance the quality of life and human dignity of all people in South Africa.

As the Credo itself says:

Ngakho-ke thina:

Sizovikela amalungelo alowo nalowo kanye nawaleso naleso sigaba sabantu bakuleli ngokusabela ngokushesha;

Sizolwela ukuqeda ukucwaswa uma kwenzeka emphakathini wethu…

Daarom sal ons:

Die fundamentele regte van elke indiwidu en elke groep in hierdie land met vasberadenheid verdedig;

Ons beywer vir die uitskakeling van diskriminasie op elke terrein waar dit voorkom…

Ladies and Gentlemen,

There is great symbolism in the celebration of this centenary.

Little more than a month after the Afrikaner Broederbond was founded in June 1918 at a home in Malvern, Johannesburg, a son was born to a chief of the abaThembu in the tiny village of Mvezo.

This young boy was called Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela and he would become the first President of the Republic of South Africa never to have been a member of the Broederbond.

We have dedicated this year to the celebration of the centenary of his birth and to the celebration of the centenary of Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu, another giant of the struggle for freedom and democracy.

Their lives – the values for which they stood and the freedoms for which they fought – stood in sharp contrast to the goals and ethos of the Broederbond.

They sought to build a society founded on the fundamental principle contained in the Freedom Charter that ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’.

This was the antithesis of the apartheid policies championed by the Broederbond from at least the 1930s and implemented with great zeal after the National Party came to power in 1948.

It was a government led by prominent members of the Broederbond who imprisoned Nelson Mandela and banned, detained and harassed Albertina Sisulu.

And it was against a government led by members of the Broederbond that Nelson Mandela, Albertina Sisulu and others mobilised a powerful movement of defiance and resistance.

It is therefore significant that it was the same Broederbond that began in the 1980s to cast doubt on the sustainability and even the morality of the system of apartheid.

It was the same Broederbond that was behind a process of reform in the National Party and in sections of white society that contributed to the release of Mandela, the unbanning of liberation movements and the negotiated transition to democracy.

It was the same Broederbond that would reconcile itself to the new democratic dispensation and would embrace the values and principles contained in our new Constitution.

The fact that we mark the centenary of the Afrikanerbond in the same year as we celebrate the centenary of the births of Nelson Mandela and Albertina Sisulu is important not only in understanding our past.

It is just as important – perhaps even more so – for understanding our future.

Nelson Mandela and Albertina Sisulu were among the most consistent proponents of a united, non-racial, non-sexist society in which all would have equal rights and opportunities.

They both believed deeply that Afrikaners were an essential and integral part of the South African nation.

They believed that South Africa belonged to all its people equally and that none should be discriminated against on the basis of language, faith, culture, creed or origin.

That is the South Africa that all of us, together, have a responsibility to build.

We owe it to the memory of Nelson Mandela and Albertina Sisulu to forge a new nation that is united in its diversity.

More importantly, we owe it to our children to forge a nation in which all may have security, all may have shelter and comfort and where all may enjoy an improving quality of life.

If we are to achieve this, we need to heed the injunction in our Constitution not only to recognise the injustices of our past but to also work together to redress them.

This means that we must strive together to realise the demand of the Freedom Charter that the people shall share in the country’s wealth.

It is this demand that stands at the centre of the economic policy of every administration since 1994, to lift the majority of South Africans out of poverty by building an inclusive economy that creates jobs.

It informs our focus on transformation, changing patterns of ownership, management and control to benefit black and women South Africans.

It informs our focus on education and skills development, on employment equity and preferential procurement.

It lies behind our determination as this government to undertake an ambitious investment drive to stimulate growth in the productive sectors of our economy.

Part of this investment drive are concrete steps to remove all the impediments to greater investment and faster growth.

As the first quarter GDP figures indicate, there is a pressing need to push forward with greater urgency to resolve policy issues in key industries like mining and telecommunications, to promote industrialisation more intensively and to advance productive land reform.

We are hard at work to deepen our efforts to stabilise state owned enterprises and set them on a path of recovery, to reduce the cost of doing business and to maintain our investment in economic and social infrastructure.

Hierdie is ‘n inisiatief waarvan die Afrikanerbond ‘n integrale deel van moet wees.

This is an effort of which the Afrikanerbond needs to be an integral part.

Die Afrikanerbond kan ‘n bydrae maak tot die groei en transformasie van die ekonomie en daardeur sy Credo verwesentlik.

It is by contributing to the growth and transformation of the economy that the Afrikanerbond can give full effect to its Credo.

One of the singular achievements of the Broederbond was the economic empowerment of the Afrikaner.

While this contributed in no small measure to the highly unequal distribution of wealth, skills and opportunity in our society, the Broederbond was responsible for unleashing the economic potential of the Afrikaner people.

Now, as we work to build an inclusive society, we look to the Afrikanerbond to play its part in unleashing the economic potential of all the people of this country.

It should do so informed by a determination to correct the injustices of the past, but based also on an understanding that a stable, prosperous and free South Africa is dependent on a more equal distribution of economic and social resources.

It should be based on an understanding that the future of the Afrikaner is inextricably linked to the prosperity and fulfilment of the people of South Africa as a whole.

Hierdie is ‘n realiteit wat die Afrikanerbond lank reeds erken en ons vertrou dat dit sy programme en aksies in die toekoms sal rig.

This is a reality that the Afrikanerbond has long appreciated and which we hope will continue to inform its programme and activities.

Hierdie is ‘n vertrekpunt wat ons benadering tot onderwys moet toelig.

This is an understanding that should inform our approach to education.

As a democratic state, we inherited a severely unequal education system which directed the bulk of resource towards white institutions.

As we know, this had a devastating effect on the social and economic capabilities of generations of black South Africans, a deficiency that continues to severely limit the development of our economy and the transformation of our society.

It was therefore imperative that the democratic government take urgent and far-reaching measures to establish an education system that benefits all South Africans equally.

We have made great progress, but we have much further to go.

As we have undertaken this task, we have had to confront the many impediments to equal access to education, including issues of poverty, distance, social norms and language.

We have had to confront the reality that many of the better resourced public schools and around a quarter of our universities were Afrikaans-medium institutions.

This proved to be a barrier to access and, had steps not been taken to change language policies at many such institutions, would have undermined our commitment to equal access to educational opportunities.

This process, as it has unfolded over the last 24 years, has caused anxiety and even dissent in some sections of the Afrikaans community.

We know that this is a matter that concerns the Afrikanerbond.

It is a concern that is to be found in many other areas where we have taken measures to end white privilege and correct past injustices, whether it be employment equity, black economic empowerment or preferential procurement.

We have a responsibility, as a society, to address these concerns.

If we do not engage on these matters and seek to find consensus, we undermine efforts to build a united society in which all feel at home.

As South Africa was preparing for its first democratic election in 1994, former Constitutional Court judge Albie Sachs wrote a paper on ‘Affirmative Action and the New Constitution’.

In the paper he said:

“The question is not whether or not to have affirmative action. Have it we must, and in a deep and meaningful way…

“If well handled, affirmative action will help bind the nation together and produce benefits for everyone. If badly managed, it will simply re-distribute resentment, damage the economy and destroy social peace. If not undertaken at all, the country will remain backward and divided at its heart.”

As we grapple with the complexity and challenge of transformation we remain guided by this sentiment.

We remain committed to affirmative action that is meaningful and improves the lives of all our people.

We remain committed in its implementation to dialogue, consultation and inclusiveness.

Hierdie is dieselfde benadering wat ons sal volg met die oplossing van die grond-vraagstuk.

This is the same approach we are taking to the resolution of the land question.

The ANC took a resolution at its 54th National Conference in December to accelerate the process of land reform.

Among the measures that government should use where appropriate is the expropriation of land without compensation.

This has generated significant debate and much interest in the question of land in South Africa.

It provides us with an opportunity to move together with purpose and determination to address one of the most contentious issues in our country’s history.

In approaching this issue, we are guided by the Freedom Charter, which said: ‘The land shall be shared among those who work it’.

I want to emphasise this point, that the land shall be shared.

The land should never have been and will not be reserved for one group of South Africans.

Our aim must be to ensure that all those who work the land – and who want to work the land – should be equally able to have such land.

By the same measure, all those who need land, whether to build a house or to run a business, should be equally able to have title to land in well-located parts of our towns and cities.

By restricting the ownership and use of land to a small minority over many decades, the apartheid government made sure that the country would never realise the full potential of this valuable resource.

It is our responsibility to unlock the economic value of the land. It is our collective responsibility to deal with and reduce poverty and inequality. We also need to acknowledge that the taking of land and removal of the majority of South Africans from their land was the source of the poverty and inequality we see.

We do so by returning land that was forcibly taken from African, coloured and Indian South Africans.

We do so by securing the rights of labour tenants to the land they have occupied for generations.

We do so by providing land close to urban centres for housing for the poor.

We do so by providing emerging farmers with finance, training and other support.

We call on all South Africans – including the members of the Afrikanerbond – to see the acceleration of land reform not as a threat, but as an opportunity.

It is an opportunity to build a more just, more equitable society that makes full and effective use of all the resources it has – its land, its mineral wealth, its oceans and, most importantly, its people.

Already, we know of several established white farmers who have found ways of sharing the land with farmworkers, labour tenants and neighbouring communities.

They have not waited for government to arrive or act.

They have taken the initiative and – with differing degrees of success –have developed different models for local land reform and agricultural development.

We commend their efforts and call on others to follow their lead.

Let us remember that

“The question is not whether or not to have land reform. Have it we must, and in a deep and meaningful way…

“If well handled, land reform will help bind the nation together and produce benefits for everyone. If badly managed, it will simply re-distribute resentment, damage the economy and destroy social peace. If not undertaken at all, the country will remain divided at its heart.”

Ladies and Gentlemen,

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the Afrikanerbond, it is inevitable that we reflect on the place and role of the Afrikaner in our history and in our democracy.

Afrikaners are by name and by definition Africans.

They are as integral to the South African nation as any other community.

Their language, their culture, their needs and their aspirations are no less important – and no more important – than those of their compatriots.

As we reflect on the last 100 years, we must acknowledge that for millions of South Africans, the Broederbond was an instrument of misery and hardship.

But as we look ahead to the next 100 years, we must be firm in our resolve that the Afrikanerbond be an instrument of unity, progress and equality.

If there is anything that our history has taught us, it is that the advancement of some cannot be achieved or sustained without the advancement of all.

Allow me to conclude by borrowing the words of Beyers Naudé, one of the finest South Africans ever to have been a member of the Broederbond.

Speaking in the days following the death in detention of Steve Biko in 1977, Oom Bey reflected on Biko’s message to fellow South Africans.

It is appropriate to recall these words, delivered over 40 years ago, because they capture in many ways the journey of the Broederbond into the Afrikanerbond, the journey of our country from apartheid to democracy.

Oom Bey said:

So, should you ask me what message Steve Biko’s life has for the Afrikaners that we should heed today, I would say it was this: break free from the prison of your subservience to an ideology that is leading our country towards disaster and that can destroy the Afrikaners as well. Break free from this ideological system that is enslaving and suffocating your whole life. Do not seek security in weapons, in an exclusive identity or in clinging to false loyalties…

Step outside and meet with black people, as they offer themselves in all sincerity to you. Grab the hand of friendship that is still being extended, even at this late hour, to you as Afrikaners and as white rulers of this country, and say to them: let us plan and determine the future of this country together.

Let us seek peace together in this torn, tragic, divided South Africa.

As we honour those who have come before us, as we pay tribute to those that lost their lives in defence of our liberty, let us heed the words of Beyers Naudé.

Laat ons saam die toekoms van hierdie land beplan en bepaal.

Laat ons saam die vrede van hierdie verskeurde, tragiese, verdeelde Suid‐Afrika soek.

Ons is almal Suid-Afrikaners, wat hierdie land saam moet bou.

Baie dankie.