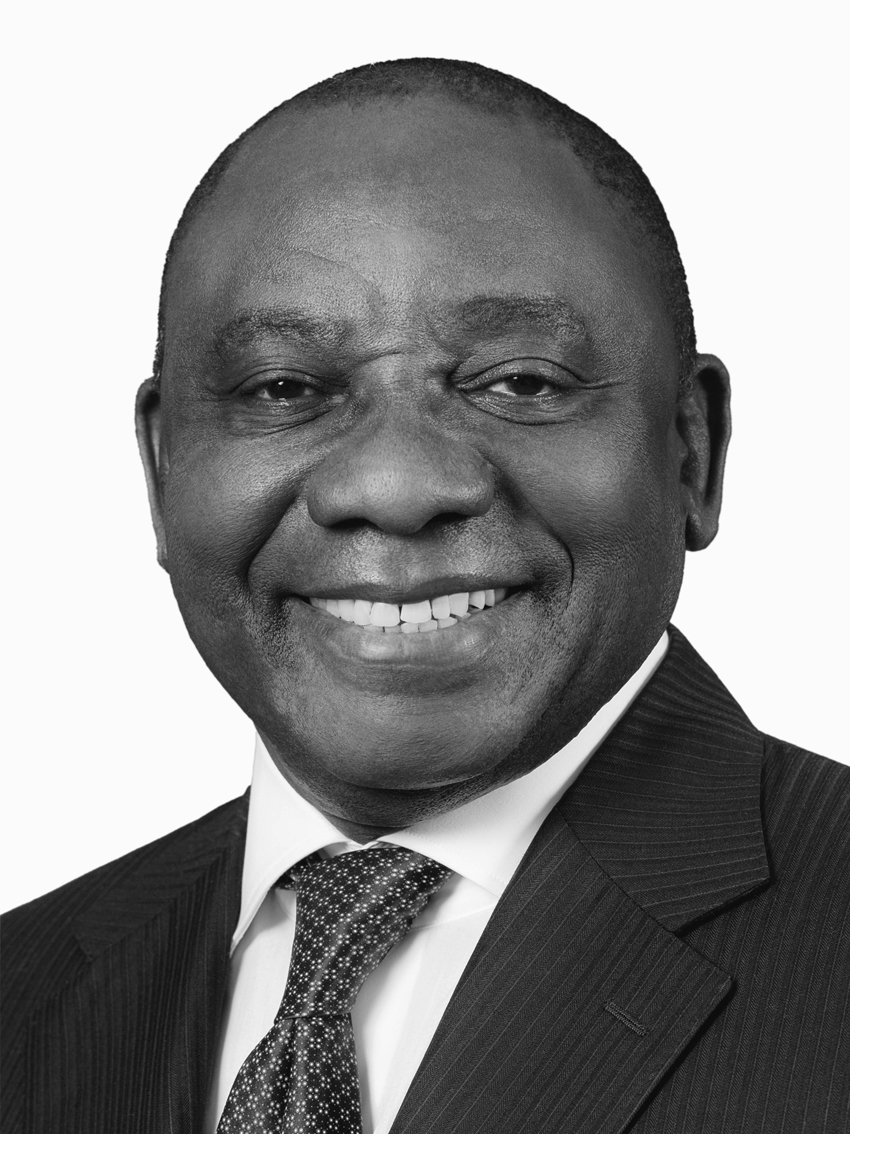

Eighth Annual Desmond Tutu International Peace Lecture delivered by President Cyril Ramaphosa, Artscape Theatre, Cape Town

Programme Director,

Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Tutu in absentia,

Mama Leah Tutu,

Archbishop Thabo Makgoba,

Members of the Tutu Family,

Leadership of the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation,

Distinguished Guests,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Fellow South Africans,

It is a great honour and a great privilege to deliver this 8th Annual Desmond Tutu International Peace Lecture.

Since its inception, this lecture has served as a platform for robust engagement on the struggle we must all wage to establish a more humane and kind world.

Allow me to express my sincere gratitude – and that of all South Africans – to Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu for a lifetime spent in the service of peace, understanding and social justice.

Yesterday, as the Arch celebrated his 87th birthday, we marvelled at the generosity of spirit, the strength of character and the love of humanity that he has exuded for as long as we have known him.

This lecture on peace, named in honour of Desmond Tutu, is taking place exactly two weeks after the United Nations held a Nelson Mandela Peace Summit at its annual General Assembly in which more than 100 heads of state and government spoke about Peace in honour of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. At the end of the debate they declared that the next decade would be the Nelson Mandela decade of peace.

This is an honour not only for Nelson Mandela but also for the work that two Nobel laureates Nelson Mandela and Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Tutu born of our great and beautiful country have done for the cause of peace. This is something that should fill us with enormous pride not arrogance; great humility and not pompousness as a nation.

As South Africans, we are privileged to be associated with these two global icons, whose extraordinary struggles earned them international recognition as torchbearers along humanity’s arduous journey towards lasting peace and stability.

Former President Nelson Mandela and Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Tutu have been beacons of hope, not only to South Africans struggling under the yoke of racial oppression, but also to the billions of people across the world who yearn for a future that is peaceful and stable.

To advance peace, we need to appreciate that at no stage in human development have people engaged in conflict without cause.

Conflict is not the natural human state.

It is the product of a set of social, political, cultural and at times religious circumstances that pits brother against brother, and – admittedly to a lesser extent – sister against sister.

If we can address those circumstances that cause war, we reduce the potential for discord and ultimately, create conditions for the end of conflict.

This was one of the central themes that emerged from the UN Nelson Mandela Peace Summit, where we argued that conflict and hostility mainly have their roots in poverty, exclusion and marginalisation.

We said that peace is not possible in an unequal world.

And no society can be at peace unless all its people have equal rights, equal opportunities and an equal quality of life.

As South Africans, we know that peace is not merely the absence of war, but also the absence of injustice.

There are still millions in our society who live in poverty, who are socially excluded and economically marginalised.

We cannot speak of true freedom when the constitutionally guaranteed rights to quality health care, to quality education, to decent housing and to a clean environment continue not to be enjoyed by many South Africans.

We cannot speak of true freedom when ten percent of the population has more wealth than the remaining 90 percent combined; when women are discriminated against at their places of work and abused in their homes; and when privilege and poverty follow the same racial contours of a colonial past.

We will not be able to say we have achieved freedom for all our people until we have corrected the historical injustice of accumulation by a minority on the basis of dispossession of the majority.

Until we do that – until we build a South Africa in which the wealth is shared among the people and the land is shared among all who work it – we will not realise lasting peace.

It is nearly 25 years since we embarked upon this part of our long journey to peace and freedom.

Having brought an end to the heinous crime of apartheid, we set out to put right the wrongs of the past and to build a new society.

An essential part of that journey was the search for truth and reconciliation, which found its manifestation in the TRC under the leadership of Archbishop Tutu.

It was rooted in the understanding that there would be no peace in our land without justice.

The TRC was in itself a key instrument of justice in a country that was in transition from a past of human rights violations to democracy.

The TRC required that the perpetrators of gross human rights abuses to account for their actions, but it also provided them with an opportunity to recognise the humanity of their victims and exposed to them the myth of racial superiority.

Burnt into our collective memory are the images of how distressed Emeritus Archbishop Tutu was as he heard evidence of the horrors and atrocities meted out against our people by agents of a murderous system that was entirely based on the false hierarchy of races.

Those images serve as a reminder that while our democratic government has done a lot to advance justice for our people since the TRC completed its work 20 years ago, the trauma of apartheid and its dark shadow lingers on in the daily lives of many of our people.

This is the trauma and dark shadow not of torture, detention or death squads, but of hunger, homelessness, illness, illiteracy and unemployment.

There are none who have seen the conditions under which so many South Africans live who could deny that the deliberate impoverishment of the black people of this country is in itself a gross human rights violation.

It is for this reason that our efforts to radically transform the South African economy and make it more inclusive should be located in the context of the restorative justice that defined the work of Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the TRC on and beyond.

In this sense, the process of truth and reconciliation will not be complete until we have acknowledged the economic and social injustices of the past, and corrected them.

This is a responsibility that falls both to those who have been the beneficiaries of racial privilege and to those who have suffered its debilitating effects.

It is a task that we need to take on together because, however divergent our respective pasts, we have a shared interest in the achievement of a just future.

We have a shared interest in the fundamental transformation of our economy and our society.

We have a shared interest in significantly and urgently reducing inequality and discrimination in all forms and manifestations.

We need to reduce the massive disparity in income and opportunity in South Africa, particularly between black and white, but also between women and men.

This requires nothing short of a skills revolution in which inclusive, accessible and relevant education produces quality outcomes.

It is essential that, alongside a skills revolution, we draw millions more young South Africans into the productive economy through work.

Last week, the social partners – government, labour, business and communities – convened a Jobs Summit, which was the culmination of several months of deliberations on measures to accelerate job creation.

It was a clear signal of the determination of all sections of society - labour, business, community and government put aside all differences and decided to work together to build a social compact to create jobs.

They decided on a number of measures and interventions which when effectively and timeously implemented will almost double the number of jobs being created each year.

Alongside the work being done by the social partners to generate employment, it is essential that our economy expands and that we are able to mobilise far greater levels of productive investment.

It is important therefore that we ensure that new investment is directed towards meaningful job creation, that local labour is prioritised, that emerging black and women entrepreneurs are supported and that communities benefit.

The dispossession of black people of their land manifested itself in a violent manner bereft of any notions of peace. Apartheid stripped black people – Africans, coloureds and Indians – of their land and their assets, impoverishing families for generations and robing them of their dignity. The evictions of farm workers especially here in the Western Cape continues unabated.

It is therefore vital, if we are to restore the dignity of our people and break the cycle of poverty that we address the land question so that there can be peace and prosperity amongst our people. This will also give us the chance to heal the wounds of the past.

It is in this context that we must understand the drive to accelerate land reform through redistribution, restitution and tenure security.

It is in the interests of both social justice and economic development that we ensure that the land is shared among all those who work it and all those who need it.

Effective land reform, where emerging farmers are provided with adequate support and poor households receive well-located land for housing in urban centres, is both a moral and economic imperative.

It unleashes great economic potential, not only of the land, but also of the people who work on it and live on it.

In our search for a just and equal society, we also need to fundamentally transform gender relations.

We cannot have a free society, we cannot have a peaceful world, for as long as women are discriminated against, exploited, neglected and abused.

We cannot tolerate the social norms and cultural practices that diminish, in any way, the equal rights and equal worth of women.

This requires a change in attitude and consciousness, a social movement that reaches into every home, classroom, workplace and relationship.

It requires policies and programmes to ensure that every girl child attends school and has every opportunity to excel, that there are no impediments for young women to complete their school and go on to higher education or training.

It means that every institution – from government department to company to university should actively work to prevent gender bias, no matter how subtle or apparently inconsequential.

We cannot have a peaceful society for as long as women are physically, verbally and emotionally abused because of their gender.

The struggle to end gender based violence must occupy all South Africans since it is fundamental to our self-worth as individuals and as a collective.

It is fundamental to our vision of a society in which all have equal rights and an equal expectation of being able to exercise them.

It is for this reason too that we cannot tolerate discrimination against any person on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The violation of the rights and equal worth of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex people demeans our common humanity.

Not only does it expose individuals to pain, suffering and even violence, but it often limits access to social services and economic opportunities for LGBTI people.

It is not possible to build a just and equal society in such circumstances.

It is our responsibility to dedicate every moment to eradicating all forms of racism, sexism, tribalism, homophobia and other intolerances.

Throughout his life, Archbishop Tutu has been a soldier for peace.

While we tend to speak about peace as a condition between nations or across a society as a whole, we often do not pay sufficient attention to peace in individual communities and in the lives of the individual citizens who make up such communities.

In this regard, I want to express appreciation and gratitude to the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation for the work it continues to do among ordinary people to secure peace in communities that are affected by many social ills, especially criminal violence.

We remain very concerned about the scourge of violent crime in many communities across the country.

This is an issue that calls for communities to come together and for religious, political and social formations and the South African Police Service to work jointly to end the bloodshed, the tears and the economic hardship that visits every family that loses its loved ones.

We must do more to reverse the impact of apartheid urban spatial design on our social fabric.

We also have to re-centre our moral compass and ask ourselves as individuals and families what we can do to improve our own lives and the lives of others in our communities.

We welcome communities that speak out and take to the streets to declare that they will not be terrorised into silence by criminals.

We commend communities that have taken action against social problems such as teenage pregnancy, substance abuse, domestic violence, gangsterism and organised crime.

Inspired by Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who has dedicated his life to securing a better future for all, let us work together as government, as labour and as communities to bring peace to our streets and homes.

From Bonteheuwel and Kensington to Westbury and Westdene, we need a social and moral regeneration that ends the violence of crime, the violence of poverty and the violence of despair.

As we carry forward the legacy of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu of building a nation that is truly at peace with itself and the world, we need voices like his to remind us of our Constitutional obligation to build a united, non-racial, non-sexist society.

We have vivid memories of Archbishop Tutu in his robes of service during his time on the streets of Soweto, downtown Johannesburg, Cape Town, Atlanta, London and many other places.

In all those images, he was always surrounded by the full spectrum of our nation.

He coined the term ‘Rainbow Nation’ not out of sentiment but out of experience, and out of the expectation that our nation would become one and remain one in perpetuity.

Let us continue building the unity of our nation, conscious always of the fact that there will be no peace without equality and no reconciliation without justice.

I want to conclude by suggesting that in honour of the outstanding work that Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Tutu has contributed in raising our consciousness about peace we should develop a doctrine of peace that should guide us to give full meaning to what peace should mean.

Peace should be about:

- Justice and fairness;

- Respecting the human rights of every human being;

- Equal opportunity to develop as a human being;

- Work fair wages and the end of poverty and inequality;

- Guns of war are silenced;

- Freedom of speech;

- Gender equality in every respect;

- Women and children are not abused;

- Accepting the diversity of humanity and being tolerant of others;

- The harmonious co-existence between people;

- Developing the skills of all citizens;

- Freedom to be whatever you want to be;

- Should be our goal in life;

- People having their own stories, thoughts and lifestyles;

- We should keep trying to find it and build it.

I thank you.