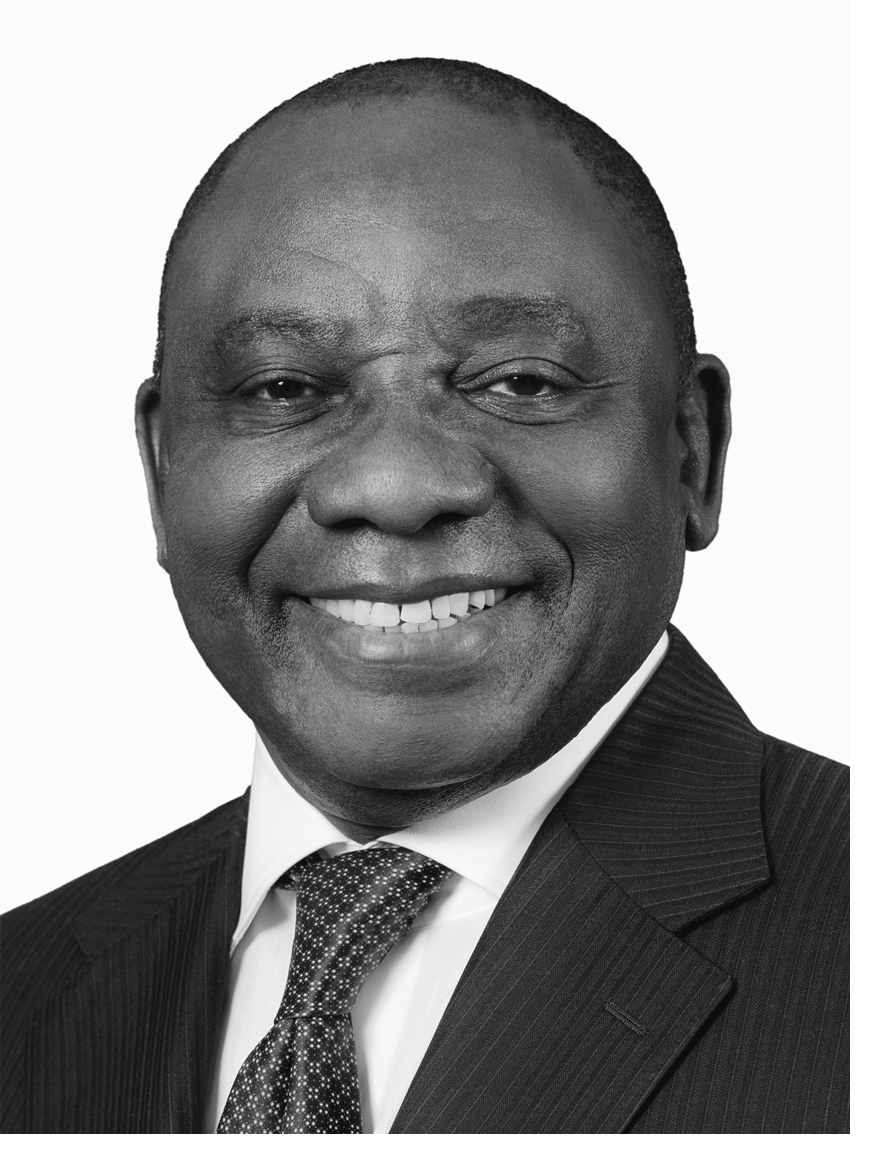

Address by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the Land Handover Ceremony, Moretele Recreation Resort, Mamelodi

Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform, Ms Maite Nkoana-Mashabane,

Ministers and Deputy Ministers,

Acting Executive Mayor of Tshwane, Cllr Richard Moheta,

MECs and councillors,

Distinguished guests,

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great honour to address this important ceremony where we celebrate the settlement of land claims.

This is a vital part of our national effort to correct the past injustice of land dispossessions.

Land reform is mandated by our Constitution and necessitated by our past.

It is important that we approach this task in an integrated and comprehensive manner – covering restitution, redistribution and tenure reform – to ensure that the land can be shared among those who work it and among those who need it.

We have embarked on a programme of accelerated land reform, which, among other things, has required that we assess the existing legislative framework.

You will recall that Members of Parliament travelled throughout our country to hear what South Africans had to say about the law and the pace of land reform.

As a result of these hearings and consultations with a number of experts, Parliament has embarked on a process to amend the Constitution to explicitly set out the circumstances in which land may be expropriated without compensation.

In this, we are guided by the rule of law and by the transformative principles of our Constitution.

We have also established an inter-ministerial committee, which is being led by the Deputy President, to oversee the accelerate land reform process.

A Presidential Advisory Panel has also been appointed to provide expert advice to assist the inter-ministerial committee.

By restoring the land to our people, we are determined that agricultural production should increase and food security shoud improve.

We are working to ensure that an environment exists for sustained agricultural growth, especially through support to young emerging black farmers.

We are today celebrating the settlement of ten land claims in Gauteng that were lodged before 31 December 1998.

Many of our people have waited for far too long for this process of land restitution and compensation to be completed.

We appreciate the patience and the perseverance of claimants, but recognise that much more needs to be done and with greater urgency.

Today is part of a process that will cover the length and breadth of this country.

We are settling land claims, returning the land to those communities and families from whom it was taken, and thereby providing the restitution that our Constitution requires.

We have been work closely across a number of government departments and agencies to ensure that more and more of these outstanding claims are addressed speedily.

Today, we are handing over the title deed to the Klipkop-Nanduna Communal Property Association on behalf of the descendants of the Mahlangu and Malobola families.

The ancestors of these families held informal or unregistered rights to the property in question and a painstaking process was followed to verify their claims.

It was found that the Malobolo family occupied the land in question from the 1800s to 1967 and the Mahlangu family from 1936 to 1960.

The painful stories of these two families echo across the country in a thousand different places, where people were deprived of their birthright, their land and their livelihoods.

The Malobola family lived on the farm known as Klipklop from the 1800s.

A piece of evidence proving the legitimacy of their occupation and their forceful removal was a letter written by the attorneys of a Mr Zwick which stated that all ‘bantu’ people at Klipkoppies were occupying the farm illegally.

They were given a mere fourteen days to remove their livestock from the farm and if they resisted, such would be impounded.

Oral evidence found that Kaflaan Andries Mahlangu was the first person from the Mahlangu family to occupy the piece of land that is now on portion 66 of the farm Klipkop.

He arrived there in 1936 with his family and they acquired labour tenancy rights on the land.

The family was dispossessed of the land they had occupied in 1960 when they were told to move to places reserved for black people.

Descendants of these families qualify for restitution of rights to the land as they occupied the farm for continuous periods of more than 10 years.

The act of returning the land to these families is therefore both symbolic and material.

It represents the righting of a grave wrong and provides this community with an opportunity to reap the benefits of a valuable asset.

In the nine other restitution settlements that we are celebrating today, the claimants chose to receive financial compensation.

In some instances, the claimants had settled elsewhere and are not in a position to start a new settlement.

In other cases, the land has been extensively developed as either industrial or residential areas.

These are the Dukathole community from Driefontein in Ekurhuleni and the Ebenezer Congregational Church in Johannesburg.

The other restitution settlements, all in Tshwane, are for the Mathabe family from Boekenhoutskloof, the Franspoort community, the Msiza family from Hondsrivier, the Kafferskraal community, the Mahlangu and Ntuli families from Tweefontein, and the Rodman community from Vygeboschlaagte.

We are engaging in this process of redress because the loss of land not only brought about poverty, but also the indignity of living without land in the place of one’s birth.

Land was a source of income, a place to graze livestock and raise crops.

It was a place to live and an asset to pass on to the next generation.

The leading intellectuals of the time raised the profound devastation that the land policies of the colonial and apartheid authorities would cause for generations.

Dr Walter Rubusana captured the enduring effects of dispossession in his collection of poetry and essays, titled Zemk' Inkomo magwalandini.

Loosely translated, it means: "There goes your heritage, you cowards."

It was a vehement call to wage a different struggle for the return of the land to those who were dispossessed.

Another writer of that age, Sol Plaatje told the story of an African family evicted from their land who had to bury a child under cover of darkness because they had “no right or title to the farmlands through which they trekked”.

He wrote:

“Even criminals dropping straight from the gallows have an undisputed claim to six feet of ground on which to rest their criminal remains, but under the cruel operation of the Natives’ Land Act little children, whose only crime is that God did not make them white, are sometimes denied that right in their ancestral home.”

The human tragedy of these laws is a source of great anguish even today, more than a century after the notorious Natives’ Land Act was enacted and 25 years into our democracy.

Families still long to have their ancestral home restored to them.

They still long for the suffering and deprivation of generations to be recognised and to receive some form of recompense.

They long to have something that they can pass on to their children after they themselves have been returned to the soil from which they were born.

We are working to ensure that where it is possible to return the land to claimants, and where they want to return to the land, that we provide the necessary support to enable them to make productive use of the land.

This is an important part of correcting the extremely skewed pattern of land ownership and land use in this country.

It is an important part of developing black farmers who can build viable businesses, create work and contribute to an agricultural revolution.

Our policies recognise that the restoration of land is not always possible and make provision for compensation to be paid instead of land.

This compensation should enable claimants to acquire other assets that can be used to retain and generate value, that can be part of our efforts over the last 25 years to address the dire levels of asset poverty among our people.

We will never fully heal the wounds of dispossession and degradation, but we are making ever greater strides in redressing the injustices visited on our people in the past.

Land reform, however, is ultimately about the future.

It is about building a South Africans which belongs to all who live in it, and in which all South Africans belong.

It is about creating new livelihoods in agriculture and ending rural poverty.

Land reform is also about building cities and towns that are integrated, where the poor have decent housing in areas close to economic opportunities.

As we accelerate the pace of land reform, we are focused also on improving the quality and the impact of our interventions.

We are working to ensure that land claims are settled much faster, and that we clear the backlog in the shortest possible time.

At the same time, we are working on better ways to ensure that the beneficiaries of restitution – like the beneficiaries of land redistribution – receive the necessary post-settlement support.

What we are witnessing today is a new South Africa being built from the ashes of the old.

We are witnessing families and communities receiving what rightfully belongs to them.

We are witnessing joy where once there was sorrow, hope where once there was despair, justice where once there was injustice.

Today, the people who once called places like Kwa Dukathole, Boekenhoutskloof, Franspoort, Hondsrivier, Kafferskraal, Tweefontein and Vygeboschlaagte home are no longer pariahs in the land of their birth, but full and equal citizens of a new united nation.

I thank you.