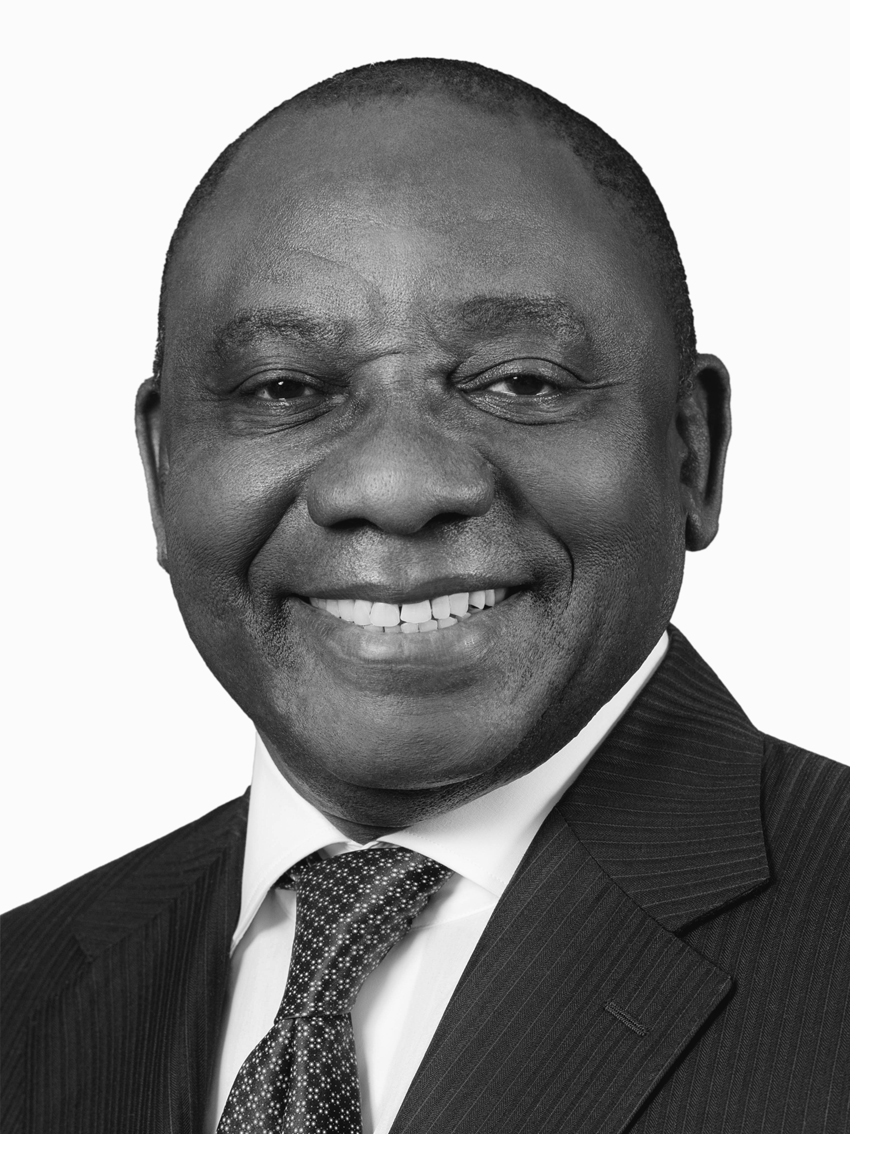

Address by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the 25 Years of Democracy Conference, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park

Programme Director, Dr Nolitha Vukuza,

Vice-Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg, Prof Tshilidzi Marwala,

Executive Director of the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection, Mr Joel Netshitenzhe,

Esteemed delegates,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I wish to thank the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection and the University of Johannesburg for convening this conference as we mark 25 years of democracy.

This conference forms part of a broader social dialogue that should enrich our understanding of the last 25 years and that contributes to a common vision and programme for the next 25 years.

Such engagement is essential if we are to forge durable and lasting social compacts across society to attain our developmental objectives.

A conference such as this one fulfils a dual purpose.

Firstly, it is an opportunity to assess progress towards the achievement of our vision of a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic, prosperous and free society.

Secondly, it is a platform to identify the challenges, opportunities and tasks of the present and the future.

In reflecting on these issues, it would be important to give consideration to the priorities, tasks and recommendations contained in the National Development Plan.

Based on an extensive diagnostic report, which provided a frank assessment of the state of the nation, the NDP sets out a vision to 2030.

It is our hope that this conference would also give attention to the programme that we have set out for the term of this 6th democratic administration.

Through the State of the Nation Address and departmental budget votes, we have described the measures that will define our developmental pathway for the next five years and beyond.

Research and academic institutions have a critical role to play in advising government, in providing the necessary data that informs our planning models.

As I said in the State of the Nation address a few weeks ago, this is a government that is not afraid of new ideas, and of new ways of thinking.

We want to work with you, and for you to challenge us, to bring added rigour to the work of government.

We look to you to continue to be a voice of both sensibility and conscience in our national life.

In his famous Reith Lecture series on Representations of the Intellectual, Edward Said posited the role of the public intellectual against what he termed ‘the insiders’.

It is these insiders, he said, “who mold public opinion, make it conformist, and encourage reliance on a superior little band of all-knowing men in power.”

The public intellectual, by contrast, does not promote special interests, but is at the forefront of questioning patriotic nationalism, corporate thinking, and a sense of class, racial and gender privilege.

The role of the public intellectual goes beyond speaking truth to power, important as that may be.

It is about providing social analysis that challenges the status quo, that interrogates the influence of vested interests in public life, and that is concerned with the production and dissemination of knowledge that is interventionist by nature.

Today, we ask that such critical analysis be directed at our experience of 25 years of nation building.

There is very little contestation of the assertion that South Africa is a vastly different place to what it was in 1994.

As a 2018 report published by the South African Institute of Race Relations notes, we are sometimes too modest about our achievements.

Titled ‘Life in South Africa: Reasons for Hope’ it highlights the remarkable progress we have made in in providing basic services and assets to the poor, in reviving and transforming our economy, in opening the doors to education and learning, in advancing non-racialism and non-sexism, and in cementing a democratic Constitutional order.

This is similarly borne out by government’s 25 Year Review, which will soon be released publicly.

In the very first years of democracy, we were called upon to address an immediate economic crisis, characterised by a substantial fiscal deficit, a huge apartheid debt bill and stagnant growth.

These challenges were underpinned by an economy that was in its design and structure simply unable to satisfy the needs of the South African people.

Through sound macroeconomic management and, to some extent, the benefits of a democratic dividend, we succeeded in turning around public finances and setting the country on an improved growth path.

Over the course of the last 25 years, however, we have been less successful in addressing the structural faults in our economy.

Thus, despite significant economic progress in the years leading up to the global financial crisis, unemployment has increased over the last decade, poverty levels have begun to rise again, and millions of South Africans remain excluded through a lack of assets, skills and networks.

The substantial investment we have made in economic and social infrastructure, in providing houses, water and electricity, in expanding access to education and health care has undoubtedly improved people’s lives.

There are several indicators of social progress, from the growth in the size of the black middle class to an improvement in educational attainment, from a massive improvement in access to basic services to a decline in levels of poverty.

However, this progress has been undermined, particularly since the global financial crisis, by stagnant growth, declining investment, maladministration and corruption, among others.

These material conditions have had an impact of the formation of a common national identity.

While we are bound together by a shared acceptance of the fundamental values of our Constitutional democracy, while we share an allegiance to the symbols of a united and free South Africa, the schisms of race, gender, class, language and ethnicity continue to run through our society.

The process of nation building – which is by definition multi-faceted and multi-layered – is therefore very much a work in progress.

Nation building has economic, political, cultural and social dimensions that are inter-related and dynamic.

Yet fundamental to the task of nation building is the removal of race, gender and class as determinants of economic and social advancement.

It is about substantially reducing inequality and creating a fairer, more just society.

As we mark 25 years of democracy, as we recognise the work that has been to establish such a society, we must acknowledge that current conditions militate against rapid progress in these areas.

Once again, our economy is in a crisis.

The optimism that characterised the early years of our democracy has been steadily eroded by disaffection and disillusionment.

The pressures of urbanisation, uneven development, the contest for resources and widespread joblessness and poverty have contributed to an increase in community protests and has weakened social cohesion.

Violence and crime continues to undermine the rights of citizens and their sense of personal security.

Corruption has steadily eroded the state’s capacity to meet people’s needs, and is worsening a trust deficit between government and the citizenry.

Local government, the coalface of service delivery, is debilitated by inefficiency, mismanagement and poor resource allocation and management.

We find ourselves at a tipping point, where worsening economic conditions threaten to erode our hard-won gains.

As Professor Steven Friedman notes in a recently published paper, although we have exceeded expectations insofar as democratic consolidation is concerned, we have yet to transform the economic patterns that exclude millions from the economy’s benefits, and the cultural patterns that preserve the power relationships created by colonisation.

So long as they are not remedied, poverty and inequality will continue to deepen.

It is our actions now that will determine the path the country takes.

If democracy is to mean more than just securing the franchise, if it is to make a material difference in people’s lives, we have to arrest the decline.

We have to ask ourselves very profound and tough questions about our democracy beyond holding regular, free and fair elections and strengthening public institutions.

We have to reflect as government particularly on whether our implementation model in its current iteration has effectively met our development needs.

In attempting to do too much, in not coordinating our actions within and between departments, we have been found wanting.

This administration has identified key tasks within a defined set of focus areas that are realistic and achievable within the next five years.

Growing an inclusive economy is by far our greatest focus.

It is a necessary condition – although not necessarily sufficient on its own – for the creation of jobs and the reduction of poverty.

We know that between 2006 and 2011, poverty declined considerably in all economic groups.

This included both the economically active and inactive, those living below the food poverty line and the population living below the upper bound poverty line.

However, poverty started rising markedly in all groups after 2015.

Our task is to arrest this rise and to reverse it.

The Economic Stimulus and Recovery Plan introduced last year, our investment drive, the measures agreed by the Jobs Summit and an ambitious plan to increase youth unemployment are all essential components of a comprehensive programme for economic recovery.

To be successful, this programme needs to be embraced and pursued by all social partners.

That is why we continue to promote broad consensus on these priorities and tasks as the foundation of social compact.

Among other things, this will require firm commitments and concessions from all sectors of society to make a practical contribution towards eradicating poverty and unemployment.

Attainment of the NDP’s Vision 2030 rests on having an educated, skilled and capable workforce.

To produce more graduates in the critical skills needed by our economy we have to work more closely with universities, TVET colleges and other educational institutions.

The National Skills Development Plan calls on all social partners to work together to invest in skills development, particularly at a time when technology is transforming the workplace.

Our efforts to reduce poverty and grow the economy require also that we improve the provision of infrastructure, resources and services to all South Africans.

This means strengthening public institutions with a specific emphasis on local government and reviewing our models of implementation and coordination.

It means that we need to improve access to affordable, quality health care, safe and reliable public transport, early childhood development and other services that are fundamental to a better quality of life.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Progress requires that we make choices.

As the new democratic government took office in 1994, it was faced with a number of stark and difficult decisions.

It needed to give practical expression to the vision of the Freedom Charter while ensuring that our new country was integrated into the global economy.

It needed to respond to the legitimate expectations of our people within a global reality – and under local circumstances – that were not conducive to a rapid improvement in the conditions of the majority of our people.

While our objective was clear, to build a country with equal rights and opportunities for all, there were sharp points of divergence on how to achieve it.

Today, 25 years later, we are reaping the consequences, both good and not so good, of those choices.

In driving this country’s development over the past quarter century, we have made policy decisions and choices that have made a real difference.

We have pursued an economic path of growth, of redress and of transformation.

This has resulted in millions more of our people being brought into the economy – and we will continue to advance policies such as Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment, employment equity and the Black Industrialists Programme as key levers of transformation.

However, crucial policy missteps have taken place.

There are instances where we failed to implement coherent policy or delayed doing so.

That is why we have decided to re-establish a Policy Unit in the Presidency to ensure that policy coordination across government is aligned.

As part of ensuring that public policy is both coordinated and evidence-based, the new unit will be working with think-tanks and research institutions, including many of those represented here.

In order to rebuild our public service, to make it more professional, and to have a corps of men and women who are ethical and skilled, our academic institutions have a similarly important role to play in the provision of training programmes and courses, working with the National School of Government.

We are alive to a host of challenges our country faces.

We are here to engage with each other on finding durable solutions.

In the end, we all have a stake in the stability and prosperity of our country.

Our elected representatives must be held to account, yes, but true nation-building requires collaboration across society.

It necessitates active and ongoing engagement.

We are first and foremost citizens, and the national interest demands that we each do our part.

We need to work together to improve the current state of affairs, to aid in nation building and the forging of a common national identity.

We need to ensure, in this context, that our academic output helps us sharpen our response to some of our most pressing challenges.

This, as Edward Said writes, is not always a matter of being a critic of government policy, but “rather of thinking of the intellectual vocation as maintaining a state of constant alertness, of a perpetual willingness not to let half-truths or received ideas steer one along.”

We look to this conference to challenge received ideas, to critically interrogate our experience of democracy over 25 years, while demonstrating a determination to be an active and interested part of charting a new path for our country.

I thank you for this opportunity and wish you all well in your deliberations over the next two days.

I thank you.